Chineese Quote if You Would Lead a Nation First Lead Your Family

| Filial piety | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

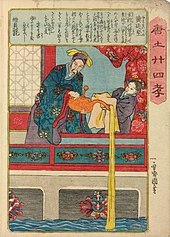

Scene from the Song Dynasty Illustrations of the Archetype of Filial Piety (detail), depicting a son kneeling before his parents.[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 孝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese proper name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | hiếu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 효 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 孝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 孝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | こう | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In Confucian, Chinese Buddhist and Taoist[two] ethics, filial piety (Chinese: 孝, xiào) is a virtue of respect for one's parents, elders, and ancestors. The Confucian Classic of Filial Piety, thought to be written around the late Warring States-Qin-Han period, has historically been the authoritative source on the Confucian tenet of filial piety. The book, a purported dialogue between Confucius and his student Zengzi, is about how to set up a good society using the principle of filial piety. Filial piety is central to Confucian role ideals.

In more full general terms, filial piety means to exist good to one'due south parents; to take care of i'due south parents; to engage in adept behave, not just towards parents just as well outside the domicile so as to bring a good name to ane's parents and ancestors; to show love, respect, and support; to display courtesy; to ensure male heirs; to uphold fraternity among brothers; to wisely advise one's parents, including dissuading them from moral unrighteousness; to display sorrow for their sickness and death; and to bury them and deport out sacrifices later on their expiry.

Filial piety is considered a key virtue in Chinese and other East Asian cultures, and it is the main subject of many stories. 1 of the near famous collections of such stories is The Twenty-four Cases of Filial Piety (Chinese: 二十四孝; pinyin: Èrshí-sì xiào ). These stories depict how children exercised their filial piety customs in the past. While China has always had a diversity of religious beliefs, filial piety custom has been common to nigh all of them; historian Hugh D.R. Baker calls respect for the family unit the one element common to almost all Chinese people.

Terminology [edit]

The western term filial piety was originally derived from studies of Western societies, based on Mediterranean cultures. However, filial piety among the ancient Romans, for example, was largely different from the Chinese in its logic and enactment.[3] Filial piety is illustrated by the Chinese character xiao (孝). The character is a combination of the character lao (old) higher up the character zi (son), that is, an elder being carried by a son.[4] This indicates that the older generation should be supported by the younger generation.[5] In Korean Confucianism, the character 孝 is pronounced hyo (효). In Vietnamese, the character 孝 is written in the Vietnamese alphabet as hiếu. In Japanese, the term is generally rendered in spoken and written language as 親孝行, oyakōkō, calculation the characters for parent and conduct to the Chinese graphic symbol to brand the word more specific.

In traditional texts [edit]

![Illustrations of the Ladies' Classic of Filial Piety (detail), Song Dynasty, depicting the section "Serving One's Parents-in-Law".[6]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a3/Illustrations_of_the_Ladies%27_Classic_of_Filial_Piety.jpg)

Illustrations of the Ladies' Archetype of Filial Piety (item), Song Dynasty, depicting the section "Serving 1's Parents-in-Law".[6]

Definitions [edit]

Confucian teachings well-nigh filial piety tin exist found in numerous texts, including the 4 Books, that is the Great Learning (Chinese: 大学), the Doctrine of the Mean (Chinese: 中庸), Analects (Chinese: 论语) and the book Mencius, also as the works Classic of Filial Piety (Chinese: 孝经) and the Volume of Rites (Chinese: 礼记) .[seven] In the Classic of Filial Piety, Confucius (551–479 BCE) says that "filial piety is the root of virtue and the basis of philosophy"[eight] and modern philosopher Fung Yu-lan describes filial piety every bit "the ideological basis for traditional [Chinese] society".[9]

For Confucius, filial piety is non merely a ritual outside respect to one'south parents, merely an in attitude every bit well.[10] Filial piety consists of several aspects. Filial piety is an awareness of repaying the burden borne by i'south parents.[xi] Equally such, filial piety is done to reciprocate the care ane'south parents accept given.[12] However, it is also practiced because of an obligation towards one's ancestors.[13] [xiv]

Co-ordinate to some modern scholars, xiào is the root of rén (仁; benignancy, humaneness),[15] but other scholars land that rén, besides as yì (義; righteousness) and li (禮; propriety) should be interpreted equally the roots of xiào. Rén means favorable beliefs to those who we are close to.[16] Yì refers to respect to those considered worthy of respect, such as parents and superiors. Li is defined as behaving according to social norms and cultural values.[16] Moreover, it is divers in the texts as deference, which is respectful submission, and reverence, meaning deep respect and awe.[ten] Filial piety was taught by Confucius as part of a wide ideal of cocky-cultivation (Chinese: 君子; pinyin: jūnzǐ ) toward being a perfect human.[17]

Modern philosopher Hu Shih argued that filial piety gained its central role in Confucian ideology simply amid after Confucianists. He proposed that Confucius originally taught the quality of rén in full general, and did not yet emphasize xiào that much. Only subsequently Confucianists such as Tseng Tzu focused on xiào as the single most important Confucianist quality.[ix]

Detailed descriptions [edit]

Confucian ideals does not regard filial piety as a selection, just rather equally an unconditional obligation of the kid.[18] The relationship between parents and children is the virtually fundamental of the five cardinal relationships (Chinese: 五倫; pinyin: wǔlún ) described by Confucius in his function ethics,[19] and filial piety, together with congenial honey, underlies this organisation.[20] It is the fundamental principle of Confucian morality:[21] filial piety was seen as the basis for an orderly society, together with loyalty of the ministers toward the ruler, and servitude of the wife toward the hubby.[22] In brusk, filial piety is central to Confucian role ideals[23] and is the cardinal virtue that defines, limits, or even eliminates all other virtues.[24]

Co-ordinate to the traditional texts, filial piety consists of physical intendance, love, service, respect, and obedience.[25] Children should effort non to bring disgrace upon their parents.[26] Confucian texts such equally Volume of Rites requite details on how filial piety should exist expert.[5] Respect is envisioned past detailed manners such equally the way children salute their parents, speak to them (words and tone used) or enter and leave the room in which their parents are, every bit well every bit seating arrangements and gifts.[27] Intendance ways making sure parents are comfortable in every single way: this involves food, accommodation, dress, hygiene, and basically to have them "meet and hear pleasurable things" (in Confucius' words)[28] and to have them alive without worry.[12] But the most important expressions of, and exercises in, filial piety were the burial and mourning rituals to be held in honour of 1'due south parents.[29] [xv]

Filial piety means to be proficient to ane'due south parents; to take care of one's parents; to engage in good conduct non just towards parents but likewise outside the home so as to bring a good name to ane's parents and ancestors;[30] to perform the duties of i'south job well (preferably the same job as ane's parents to fulfill their aspirations)[12] as well as to carry out sacrifices to the ancestors;[31] to not be rebellious;[fourteen] to be polite and well-mannered; to show love, respect, and support; to be near habitation to serve i'south parents;[32] to display courtesy;[28] to ensure male heirs[12] and uphold fraternity among brothers;[ commendation needed ] to wisely advise 1's parents, including dissuading them from moral unrighteousness;[32] to display sorrow for their sickness and death;[33] and to bury them and comport out sacrifices after their decease.[34] Furthermore, a filial child should promote the public name of its family, and it should cherish the affection of its parents.[12]

Traditional texts essentially draw filial piety in terms of a son–father relationship, but in practice, it involves all parent–child relationships, also as relationships with stepparents, grandparents and ancestors.[35]

But filial piety besides involves the role of the parent to the kid. The father has a duty to provide for the son, to teach him in traditions of ancestor worship, to detect a spouse for him, and to exit a good heritage.[36] [35] A father is supposed to be 'stern and dignified' to his children, whereas a mother is supposed to be 'gentle and compassionate'. The parents' virtues are to be practiced, regardless of the child's piety, and vice versa.[35] Nonetheless, filial piety mostly identified the child'due south duty, and in this, information technology differed from the Roman concept of patria potestas, which defined more often than not the begetter's authoritative power. Whereas in Roman culture, and later in the Judeo-Christian West, people in authority legitimized their influence by referring to a higher transcending power, in Chinese culture, potency was defined past the roles of the subordinates (son, subject, married woman) to their superior (male parent, emperor, husband) and vice versa. As roles and duties were depersonalized, supremacy became a matter of role and position, rather than person, as it was in the West.[37]

Anthropologist Francis Hsu argued that a child'south obedience from a Confucian perspective was regarded as unconditional, just anthropologist David K. Jordan and psychologist David Yau-fai Ho disagree.[35] [14] Hashemite kingdom of jordan states that in classical Chinese thought, 'remonstrance' was part of filial piety, meaning that a pious kid needs to dissuade a parent from performing immoral deportment.[35] Ho points out in this regard that the Confucian classics do not advocate 'foolish filial piety' (愚孝 pinyin: yúxiào ).[14] However, Jordan does add together that if the parent does not mind to the child's dissuasion, the child must even so obey the parent,[38] and Ho states that "rebellion or outright defiance" is never approved in Confucian ethics.[xiv]

Filial piety not just extends to beliefs of children toward their parents, just also involves gratitude toward the human torso they received from their parents,[21] [39] equally the body is seen equally an extension of ane's parents.[32] This involves prohibitions on dissentious or pain the torso, and this doctrine has affected how the Confucianists regarded the shaving of the caput by Buddhist monks,[21] but also has created a taboo on suicide, regarded every bit 'unfilial beliefs' (不孝 pinyin: bùxiào ).[twoscore]

Relation with guild at large [edit]

A memorial rock at a Korean elementary school, with the inscription "filial piety".

Filial piety is regarded as a principle that ordered society, without which anarchy would prevail.[22] It is described equally "an inevitable fact of nature", as opposed to mere convention,[41] and it is seen to follow naturally out of the begetter–son relationship.[42] In the Chinese tradition of patriarchy, roles are upheld to maintain the harmony of the whole.[43] According to the Neo-Confucian philosopher Cheng Hao (1032–1085 CE), relationships and their respective roles "belong to the eternal principle of the creation from which there is no escape between heaven and earth".[44]

The idea of filial piety became pop in China considering of the many functions it had and many roles information technology undertook, as the traditional Confucian scholars such equally Mencius (quaternary century BCE) regarded the family every bit a fundamental unit that formed the root of the nation. Though the virtue of xiào was almost respect by children toward their parents, it was meant to regulate how the young generation behaved toward elders in the extended family unit and in society in general.[45] [46] Furthermore, devotion to one'due south parents was oft associated with one'southward devotion to the state,[note 1] described as the "parallel formulation of society"[47] or the "Model of Ii".[20] The Classic of Filial Piety states that an obedient and filial son volition grow up to become a loyal official (pinyin: chung )—filial piety was therefore seen as a truth that shaped the citizens of the state,[22] and the loyalty of the minister to his emperor was regarded as the extension of filial piety.[48] Filial piety was regarded as being a dutiful person in full general.[44]

Withal, the two were not equated. Mencius teaches that ministers should overthrow an immoral tyrant, should he harm the land—the loyalty to the king was considered provisional, not as unconditional as in filial piety towards one parents.[18]

In East Asian languages and cultures [edit]

Confucian teachings about filial piety have left their mark on Eastward Asian languages and culture. In Chinese, there is a saying that "among hundreds of behaviors, filial piety is the most important 1" (Chinese: 百善孝为先; pinyin: bǎi shàn xiào wéi xiān ).[46] [eight]

In modern Chinese, filial piety is rendered with the words Xiào shùn (孝顺), meaning 'respect and obedience'.[49] While China has always had a diverseness of religious beliefs, filial piety has been common to well-nigh all of them; historian Hugh D.R. Bakery calls respect for the family unit the ane element mutual to well-nigh all Chinese people.[50] Historian Ch'ü T'ung-tsu stated almost the codified of patriarchy in Chinese law that "[i]t was all a question of filial piety".[51] Filial piety also forms the basis for the veneration of the aged, for which the Chinese are known.[xiv] [ix] Withal, filial piety among the Chinese has led them to exist generally focused on taking intendance of close kin, and be less interested in wider problems of more distant people:[xiii] [52] nonetheless, this should not be mistaken for individualism. In Japan, yet, devotion to kinship relations was and even so is much more broadly construed, involving more than only kin.[13]

In Korean civilisation, filial piety is as well of crucial importance.[53] In Taiwan, filial piety is considered 1 of eight important virtues, amidst which filial piety is considered supreme. It is "central in all thinking about human behavior".[8] Taiwan mostly has more traditional values with regard to the parent–child relationship than the People's Republic of China (Prc). This is reflected in attitudes about how desirable it is for the elderly to live independently.[54]

In behavioral sciences [edit]

Social scientists have washed much research about filial piety and related concepts.[55] Information technology is a highly influential gene in studies about Asian families and intergenerational studies, every bit well equally studies on socialization patterns.[5] Filial piety has been defined by several scholars as the recognition past children of the aid and intendance their parents take given them, and the respect returned by those children.[56] Psychologist Chiliad.Due south. Yang has defined it as a "specific, complex syndrome or prepare of cognition, affects, intentions, and behaviors concerning being practiced or dainty to ane's parents".[57] As of 2006, psychologists measured filial piety in inconsistent ways, which has prevented much progress from existence made.[5]

Filial piety is divers by behaviors such as daily maintenance, respect and sickness care offered to the elderly.[55] Although in scholarly literature 5 forms of reverence take been described, multi-cultural researcher Kyu-taik Sung has added 8 more to that, to fully cover the traditional definitions of elder respect in Confucian texts:[58]

- Intendance respect: making sure parents are comfortable in every single style;

- Victual respect: taking the parents' preferences into business relationship, e.g. favorite food;

- Gift respect: giving gifts or favors, e.g. presiding meetings;

- Presentational respect: polite and appropriate decorum;

- Linguistic respect: apply of honorific language;

- Spatial respect: having elders sit down at a place of honor, edifice graves at respectful places;

- Celebrative respect: jubilant birthdays or other events in laurels of elders;

- Public respect: voluntary and public services for elders;

- Amenable respect: listening to elders without talking back;

- Consultative respect: consulting elders in personal and family unit matters;

- Salutatory respect: bowing or saluting elders;

- Precedential respect: allowing elders to have priority in distributing appurtenances and services;

- Funeral respect: mourning and burying elders in a respectful way;

- Ancestor respect: commemorating ancestors and making sacrifices for them.

These forms of respect are based on qualitative enquiry.[59] Some of these forms involve some activity or work, whereas other forms are more symbolic. Female elders tend to receive more than intendance respect, whereas male person elders tend to receive more symbolic respect.[60]

Apart from attempting to define filial piety, psychologists have likewise attempted to explain its cognitive development. Psychologist R.Thousand. Lee distinguishes a 5-fold evolution, which he bases on Lawrence Kohlberg's theory of moral development. In the kickoff stage, filial piety is comprehended equally merely the giving of textile things, whereas in the second stage this develops into an understanding that emotional and spiritual support is more important. In the tertiary phase, the kid realizes that filial piety is crucial in establishing and keeping parent–child relationships; in the 4th stage, this is expanded to include relationships exterior of one's family. In the final phase, filial piety is regarded as a ways to realize one's ethical ideals.[61]

Psychologists have found correlations between filial piety and lower socio-economic condition, female person gender, elders, minorities, and non-westernized cultures. Traditional filial piety beliefs take been connected with positive outcomes for the community and guild, care for elder family unit members, positive family relationships and solidarity. On the other side, information technology has also been related to an orientation to the past, resistance to cognitive alter, superstition and fatalism; dogmatism, authoritarianism and conformism, as well as a conventionalities in the superiority of one's culture; and lack of active, critical and artistic learning attitudes.[62] Ho connects the value of filial piety with authoritarian moralism and cerebral conservatism in Chinese patterns of socialization, basing himself on findings amid subjects in Hong Kong and Taiwan. He defines authoritarian moralism as hierarchical authority ranking in family and institutions, as well equally the pervasiveness of using moral precepts every bit criteria of measuring people. Cognitive moralism he derives from social psychologist Anthony Greenwald, and means a "disposition to preserve existing knowledge structures" and resistance to change. He concludes that filial piety appears to take a negative event on psychological development, but at the same time, partly explains the loftier motivation of Chinese people to attain academic results.[63]

In family counselling enquiry, filial piety has been seen to help establish bonding with parents.[64] Ho argues that the value filial piety brings along an obligation to raise i's children in a moral way to prevent disgrace to the family.[65] However, filial piety has too been found to perpetuate dysfunctional family patterns such as child abuse: there may exist both positive and negative psychological effects.[66] Francis Hsu made the argument that when taken to the level of the family unit at large, pro-family attitudes informed by filial piety tin lead to nepotism, corruption and somewhen are at tension with the expert of the state every bit whole.[67]

In Chinese parent–kid relations, the aspect of dominance goes hand-in-hand with the aspect of benevolence. E.g. many Chinese parents back up their children's education fully and do not allow their children to piece of work during their studies, assuasive them to focus on their studies. Because of the combination of benevolence and authoritarianism in such relations, children feel obliged to respond to parents' expectations, and internalize them.[68] Ho found, still, that in Chinese parent–child relations, fear was likewise a contributing gene in meeting parents' filial expectations: children may not internalize their parents' expectations, only rather perform roles every bit skilful children in a detached fashion, through affect–role dissociation.[69] Studying Korean family relations, scholar Dawnhee Yim argues that internalization of parents' obligations past children may atomic number 82 to guilt, equally well as suppression of hostile thoughts toward parents, leading to psychological problems.[70] Hashemite kingdom of jordan establish that despite filial piety being asymmetrical in nature, Chinese interviewees felt that filial piety contained an element of reciprocity: "... it is easy to see the parent whom one serves today as the self who is served tomorrow." Furthermore, the practice of filial piety provides the pious kid with a sense of adulthood and moral heroism.[71]

History [edit]

Pre-Confucian history [edit]

The origins of filial piety in East Asia lie in ancestor worship,[fifteen] and can already be found in the pre-Confucian period. Epigraphical findings such as oracle basic contain references to filial piety; texts such as the Classic of Changes (10th–fourth century BCE) may contain early references to the thought of parallel conception of the filial son and the loyal minister.[72]

Early Confucianism [edit]

In the T'ang dynasty (6th–10th century), not performing filial piety was declared illegal, and even earlier, during the Han dynasty (2d century BCE–3rd century CE), this was already punished past beheading.[26] Behavior regarded as unfilial such every bit mistreating or abandoning ane's parents or grandparents, or refusing to complete the mourning period for them was punished past exile and beating, at best.[73]

From the Han Dynasty onward, the exercise of mourning rites came to be seen as the cornerstone of filial piety and was strictly practiced and enforced. This was a period of unrest, and the state promoted the practice of long-term mourning to reestablish their say-so. Filial piety toward one's parents was expected to atomic number 82 to loyalty to the ruler, expressed in the Han proverb "The Emperor rules all-under-heaven with filial piety".[47] Government officials were expected to accept leave for a mourning period of two years afterward their parents died.[74] Local officials were expected to encourage filial piety to 1'southward parents—and by extension, to the state—by behaving as an instance of such piety.[75] Indeed, the king himself would perform an exemplary role in expressing filial piety, through the ritual of 'serving the elderly' (pinyin: yang lao zhi li ). Nigh all Han emperors had the word xiào in their temple name.[29] [76] The promotion of filial piety in this way, as function of the idea of li, was more than an adequate way to create society in order than resorting to law.[77]

Filial piety became a keystone of Han morality.[76]

During the early Confucian menstruum, the principles of filial piety were brought back past Japanese and Korean students to their respective homelands, where they became central to the didactics system. In Nihon, rulers gave awards to people deemed to practice exemplary filial deport.[36]

During the Mongolian rule in the Yuan dynasty (13th–14th century), the practice of filial piety was perceived to deteriorate. In the Ming dynasty (14th–17th century), emperors and literati attempted to revive the community of filial piety, though in that process, filial piety was reinterpreted, as rules and rituals were modified.[78] Even on the grassroots level a revival was seen, as societies that provided vigilance against criminals started to promote Confucian values. A book that was composed past members of this movement was The Twenty-four Cases of Filial Piety.[79]

Introduction of Buddhism [edit]

Buddha image with scenes of stories in which he repaid his parents. Baodingshan, Dazu, Prc

Filial piety is an of import aspect of Buddhist ethics since early Buddhism,[fourscore] and was essential in the apologetics and texts of Chinese Buddhism.[81] In the Early Buddhist Texts such as the Nikāyas and Āgamas, filial piety is prescribed and practiced in three ways: to repay the gratitude toward i's parents; as a good karma or merit; and as a way to contribute to and sustain the social social club.[82] In Buddhist scriptures, narratives are given of the Buddha and his disciples practicing filial piety toward their parents, based on the qualities of gratitude and reciprocity.[83] [84] Initially, scholars of Buddhism like Kenneth Ch'en saw Buddhist teachings on filial piety every bit a distinct characteristic of Chinese Buddhism. Afterward scholarship, led by people such as John Strong and Gregory Schopen, has come to believe that filial piety was function of Buddhist doctrine since early on times. Strong and Schopen accept provided epigraphical and textual evidence to show that early on Buddhist laypeople, monks and nuns often displayed strong devotion to their parents, concluding filial piety was already an important part of the devotional life of early Buddhists.[85] [86]

When Buddhism was introduced in Cathay, information technology had no organized celibacy.[87] Confucianism emphasized filial piety to parents and loyalty to the emperor, and Buddhist monastic life was seen to go against its tenets.[88] In the 3rd–5th century, equally criticism of Buddhism increased, Buddhist monastics and lay authors responded past writing about and translating Buddhist doctrines and narratives that supported filiality, comparing them to Confucianism and thereby defending Buddhism and its value in society.[89] The Mouzi Lihuolun referred to Confucian and Daoist classics, also as historical precedents to reply to critics of Buddhism.[90] The Mouzi stated that while on the surface the Buddhist monk seems to pass up and carelessness his parents, he is really aiding his parents as well every bit himself on the path towards enlightenment.[91] Lord's day Chuo (c.300–380) further argued that monks were working to ensure the salvation of all people and making their family proud by doing so,[91] and Liu Xie stated that Buddhists expert filial piety past sharing merit with their departed relatives.[92] Buddhist monks were besides criticized for not expressing their respect to the Chinese emperor by prostrating and other devotion, which in Confucianism was associated with the virtue of filial piety. Huiyuan (334–416) responded that although monks did not express such piety, they did pay homage in heart and listen; moreover, their teaching of morality and virtue to the public helped support purple rule.[93] [94]

From the 6th century onward, Chinese Buddhists began to realize that they had to stress Buddhism'southward own particular ideas about filial piety in order to for Buddhism to survive.[95] Śyāma, Sujāti and other Buddhist stories of cocky-sacrifice spread a belief that a filial kid should even exist willing to sacrifice its own body.[96] [95] The Ullambana Sūtra introduced the idea of transfer of merit through the story of Mulian Saves His Mother and led to the establishment of the Ghost Festival. By this Buddhists attempted to show that filial piety also meant taking intendance of ane's parents in the adjacent life, not simply this life.[97] Furthermore, authors in Mainland china— and Tibet, and to some extent Nihon—wrote that in Buddhism, all living beings have one time been one's parents, and that practicing compassion to all living beings every bit though they were 1'due south parents is the more superior form of filial piety.[98] Some other aspect emphasized was the bully suffering a mother goes through when giving birth and raising a child. Chinese Buddhists described how hard information technology is to repay the goodness of ane's mother, and how many sins mothers often committed in raising her children.[99] The mother became the primary source of well-beingness and indebtedness for the son, which was in dissimilarity with pre-Buddhist perspectives emphasizing the male parent.[100] Nevertheless, although some critics of Buddhism did not have much touch during this time, this inverse in the period leading up to the Neo-Confucianist revival, when Emperor Wu Zong (841–845) started the Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution, citing lack of filial piety as one of his reasons for attacking Buddhist institutions.[101]

Filial piety is withal an important value in a number of Asian Buddhist cultures. In China, Buddhism connected to uphold a office in state rituals and mourning rites for ancestors, up until late imperial times (13th–20th century).[102] Also, sūtras and narratives about filial piety are still widely used.[94] The Ghost Festival is nonetheless popular in many Asian countries, particularly those countries which are influenced by both Buddhism and Confucianism.[103]

Tardily majestic period [edit]

During the 17th century, some missionaries tried to foreclose Chinese people from worshiping their ancestors. This was regarded every bit an set on on Chinese culture.[15]

During the Qing dynasty, however, filial piety was redefined by the emperor Kangxi (1654–1722), who felt it more of import that his officials were loyal to him than that they were filial sons: civil servants were often not allowed to go on extended leave to perform mourning rituals for their parents. The parallel conception of club therefore disappeared from Chinese society.[104]

Unlike western societies, patriarchalism and its enactment in police grew more strict in belatedly regal People's republic of china. The duties of the obedient child were much more than precisely and rigidly prescribed, to the extent that legal scholar Hsu Dau-lin argued almost this period that it "engendered a highly disciplinarian spirit which was entirely alien to Confucius himself". Indeed, the tardily royal Chinese held patriarchalism loftier as an organizing principle of society, as laws and punishments gradually became more strict and astringent.[105]

Just during the aforementioned time, in Japan, a classic piece of work about filial practices was compiled, called Biographies of Japanese Filial Children (Japanese pronunciation: Fu San Ko Shi Dan).[36]

19th–20th century [edit]

During the rise of progressivism and communism in China in the early 20th century, Confucian values and family-centered living were discouraged by the state and intellectuals.[19] During the New Culture Motion of 1911, Chinese intellectuals and strange missionaries attacked the principle of filial piety, the latter considering it an obstruction of progress.[24]

In Nihon, filial piety was not regarded equally an obstacle to modernization, though scholars are in disagreement as to why this was the case.[36] Francis Hsu believed that "the human networks through which it plant concrete expressions" were dissimilar in Japan, and there never was a motility against filial piety as there was in Communist china.[36]

The late purple tendency of increased patriarchalism fabricated information technology difficult for the Chinese to build stiff patrimonial groups that went beyond kin.[106] Though filial piety was practiced much in both countries, the Chinese manner was more limited to close kin than in Japan. When industrialization increased, filial piety was therefore criticized more than in China than in Japan, because Mainland china felt it limited the way the country could meet the challenges from the West.[107] For this reason, China adult a more than critical stance towards filial piety and other aspects of Confucianism than other East Asian countries, including not only Nihon, but also Taiwan.

In the 1950s, Mao Zedong's socialist measures led to the dissolution of family unit businesses and more dependence on the state instead; Taiwan's socialism did not go that far in state control.[108]

Ethnographic prove from the 19th and early on 20th century shows that Chinese people still very much cared for their elders, and very often lived with i or more married sons.[109]

Developments in modern lodge [edit]

In 21st-century Chinese societies, filial piety expectations and practice have decreased. 1 crusade for this is the rise of the nuclear family unit without much co-residence with parents. Families are condign smaller because of family planning and housing shortages. Other causes of decrease in practice are individualism, the loss of status of elderly, emigration of young people to cities and the independence of young people and women.[110] To amplify this trend, the number of elderly people has increased chop-chop.[19]

The relationship between hubby and wife came to exist more than emphasized, and the extended family less and less. Kinship ties betwixt the husband and married woman'southward families take become more bi-lateral and equal.[111] The way respect to elders is expressed is also irresolute. Communication with elders tends to go more reciprocal and less one-style, and kindness and courtesy is replacing obedience and subservience.[112]

Intendance-giving [edit]

Stone headrest with scenes of filial piety, Ming dynasty (1368–1644)

In modern Chinese societies, elder care has changed much. Studies have shown that there is a discrepancy between the parents' filial expectations and the actual behaviors of their children.[55] The discrepancy with regard to respect shown past the children makes elderly people especially unhappy.[55] [5] Industrialization and urbanization have afflicted the do of filial piety, with care being given more than in fiscal means rather than personal.[five] Just as of 2009, care-giving of the young to elderly people had not undergone any revolutionary changes in Mainland Communist china, and family obligations nevertheless remained strong, still "near automatic".[113] Respect to elders remains a central value for Eastward Asian people.[114]

Comparing data from the 1990s from Taiwan and the PRC, sociologist Martin Whyte concluded that the elderly in Taiwan often received less support from the government, but more assistance from their children, than in China, despite the former being an economically more modern nation.[115]

Work ethos and business practices [edit]

In mainland Chinese concern civilization, the culture of filial piety is decreasing in influence. As of 2003, western-style business organisation practices and managerial style were promoted by the Chinese government to modernize the country.[116] Still, in Japan, employees commonly regard their employer every bit a sort of begetter, to which they feel obliged to express filial devotion.[117]

Relation with police [edit]

In some societies with large Chinese communities, legislation has been introduced to found or uphold filial piety. In the 2000s, Singapore introduced a law that makes it an offense to refuse to support 1'southward elderly parents; Taiwan has taken like punitive measures. Hong Kong, on the other paw, has attempted to influence its population by providing incentives for fulfilling their obligations. For example, certain tax allowances are given to citizens that are willing to live with their elderly parents.[118]

Some scholars have argued that medieval China's reliance on governance by filial piety formed a social club that was ameliorate able to forestall law-breaking and other misconduct than societies that did so but through legal means.[77]

East Asian immigrants [edit]

Chinese who immigrate to the United States more often than not continue to ship money to their parents out of filial piety.[119]

See also [edit]

- Family as a model for the state

- Laurels thy father and thy mother

Notes [edit]

- ^ Encounter Analects ane:two, Xiao Jing (chap.one)

References [edit]

- ^ Ebrey, Patricia Buckley. "Paintings with political agendas". A Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilisation . Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ Kohn 2004, passim.

- ^ Hamilton 1990, pp. 78, 84.

- ^ Ikels 2004, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b c d e f Yee 2006.

- ^ Mann & Cheng 2001, p. 46.

- ^ Sung 2009a, pp. 179, 186–vii.

- ^ a b c Jordan 1998, p. 267.

- ^ a b c King & Bail 1985, p. 33.

- ^ a b Sung 2001, p. 15.

- ^ Cong 2004, p. 158.

- ^ a b c d due east Kwan 2000, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Hsu 1998, p. 63.

- ^ a b c d e f Ho 1994, p. 350.

- ^ a b c d Hsu, O'Connor & Lee 2009, p. 159.

- ^ a b Kwan 2000, p. 31.

- ^ Hsu, O'Connor & Lee 2009, pp. 158–9.

- ^ a b Fung & Cheng 2010, p. 486.

- ^ a b c Sung 2009a, p. 180.

- ^ a b Oh 1991, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Sung 2009b, p. 355.

- ^ a b c Kutcher 2006, p. 13.

- ^ Chang & Kalmanson 2010, p. 68.

- ^ a b Hsu 1998, p. 61.

- ^ Run across Kwan (2000, p. 24), Yee (2006) and Sung (2009a, p. 187). Only Kwan mentions love.

- ^ a b Cong 2004, p. 159.

- ^ See Sung (2001, p. sixteen) and Sung (2009a, p. 187). Just his 2001 article mentions the seats and gifts.

- ^ a b Sung 2001, pp. 15–6.

- ^ a b Kutcher 2006, p. xiv.

- ^ Sung 2001, p. 17.

- ^ Sung 2001, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Kwan 2000, p. 24.

- ^ Sung 2001, pp. xvi–7.

- ^ Kutcher 2006, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e Jordan 1998, p. 269.

- ^ a b c d eastward Hsu 1998, p. 62.

- ^ Hamilton 1990, p. 92–4.

- ^ Jordan 1998, pp. 270.

- ^ 《孝經》:"'身體髮膚,受之父母,不敢毀傷,孝之始也。'". Xiaojing: "[Confucius said to Zengzi]: 'Your torso, including hair and skin, you have received from your begetter and mother, and you should not dare to harm or destroy it. This is the start of xiao.'"

- ^ See Sun, Long & Boore (2007, p. 256). Hamilton (1990, p. 102, note 56) offers this rendering in English.

- ^ Jordan 1998, p. 278.

- ^ Hamilton 1990, p. 84.

- ^ Hamilton 1990, p. 93.

- ^ a b Hamilton 1990, p. 95.

- ^ Chow 2009, p. 320.

- ^ a b Wang, Yuen & Slaney 2008, p. 252.

- ^ a b Kutcher 2006, p. ii.

- ^ Hamilton 1990, p. 100, north.2.

- ^ Baker 1979, p. 98.

- ^ Hamilton 1990, p. 92.

- ^ Hamilton 1990, p. 91.

- ^ Yim 1998, p. 165.

- ^ Whyte 2004, p. 123.

- ^ a b c d Fung & Cheng 2010, p. 315.

- ^ Sung 2001, p. 14.

- ^ Kwan 2000, p. 23.

- ^ Sung 2001, pp. 17–8.

- ^ Sung 2001, p. nineteen.

- ^ Sung 2001, pp. 22–4.

- ^ Kwan 2000, p. 29.

- ^ For the resistance to change and attitudes of superiority, meet Kwan (2000, pp. 27, 34). For the other consequences, see Yee (2006). Ho (1994, p. 361) besides describes the link with resistance to change, the learning attitudes, fatalism, dogmatism, authoritarianism and conformism.

- ^ Ho 1994, pp. 351–ii, 362.

- ^ Kwan 2000, p. 27.

- ^ Ho 1994, p. 361.

- ^ Kwan 2000, pp. 27, 34–five.

- ^ Hashemite kingdom of jordan 1998, p. 276.

- ^ Kwan 2000, p. 32.

- ^ Kwan 2000, p. 33.

- ^ Yim 1998, pp. 165–6.

- ^ Jordan 1998, p. 274–5.

- ^ Kutcher 2006, p. 12.

- ^ Hamilton 1990, pp. 102–three, due north.56.

- ^ Kutcher 2006, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Kutcher 2006, pp. 2, 12.

- ^ a b Chan & Tan 2004, p. 2.

- ^ a b Kutcher 2006, p. 194.

- ^ Kutcher 2006, p. 35.

- ^ Kutcher 2006, p. 45.

- ^ Potent 1983.

- ^ Ch'en 1973.

- ^ Xing 2016, p. 214.

- ^ Xing 2016, p. 220.

- ^ Xing 2012, p. 83.

- ^ Schopen 1997, pp. 57, 62, 65–7.

- ^ Strong 1983, pp. 172–three.

- ^ Zurcher 2007, p. 281.

- ^ Ch'en 1968, p. 82.

- ^ Ch'en 1968, pp. 82–three.

- ^ Xing 2018, p. ten.

- ^ a b Kunio 2004, pp. 115–half dozen.

- ^ Xing 2018, p. 12.

- ^ Ch'en 1968, p. 94.

- ^ a b Xing 2016, p. 224.

- ^ a b Strong 1983, p. 178.

- ^ Knapp 2014, pp. 135–half-dozen, 141, 145.

- ^ Wilson 2014, p. 194.

- ^ Li-tian 2010, pp. 41, 46.

- ^ Idema 2009, p. xvii.

- ^ Cole 1994, p. 2.

- ^ Smith 1993, pp. 7, 10–one.

- ^ Smith 1993, pp. 12–iii.

- ^ Truitt 2015, p. 292.

- ^ Kutcher 2006, p. 120.

- ^ Hamilton 1990, pp. 87–8, 97.

- ^ Hamilton 1990, p. 97.

- ^ Hsu 1998, p. 67.

- ^ Whyte 2004, pp. 107–viii.

- ^ Whyte 2004, p. 106.

- ^ Encounter Fung & Cheng (2010, p. 315) for the nuclear family, individualism, loss of status, emigration and female independence. Come across Sung (2009a, p. 180) for the causes of the rise of the nuclear family and the independence of immature people.

- ^ Whyte 2004, p. 108.

- ^ Sung 2001, p. 21.

- ^ Sung 2009a, pp. 181, 185.

- ^ Sung 2001, p. 22.

- ^ Whyte 2004, pp. 117–8.

- ^ Fu & Tsui 2003, p. 426.

- ^ Oh 1991, p. 50.

- ^ Grub 2009, pp. 319–20.

- ^ Hsu 1985, p. 99.

Bibliography [edit]

- Baker, Hugh D. R. (1979), Chinese Family unit and Kinship, Columbia University Press

- Chan, Alan Kam-leung; Tan, Sor-hoon (2004), "Introduction", Filial Piety in Chinese Thought and History, Psychology Press, p. 1–xi, ISBN978-0-415-33365-viii

- Ch'en, Kenneth (1968), "Filial Piety in Chinese Buddhism", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 28: 81–97, doi:x.2307/2718595, ISSN 0073-0548, JSTOR 2718595

- Chang, Wonsuk; Kalmanson, Leah (8 November 2010), Confucianism in Context: Classic Philosophy and Gimmicky Issues, East asia and Across, SUNY Printing, ISBN978-1-4384-3191-eight

- Ch'en, One thousand. (1973), The Chinese Transformation of Buddhism, Princeton University Printing

- Chow, Northward. (2009), "Filial Piety in Asian Chinese Communities", in Sung, K.T.; Kim, B.J. (eds.), Respect for the Elderly: Implications for Human Service Providers, University Press of America, pp. 319–24, ISBN978-0-7618-4530-0

- Cole, R. Alan (1994), Mothers and Sons in Chinese Buddhism, Stanford University Press, ISBN978-0-8047-6510-7

- Cong, Y. (2004), "Md–family unit–patient Human relationship: The Chinese Paradigm of Informed Consent", The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 29 (2): 149–78, doi:10.1076/jmep.29.2.149.31506, PMID 15371185

- Fu, P.P.; Tsui, A.South. (2003), "Utilizing Printed Media to Sympathise Desired Leadership Attributes in the People's Republic of China", Asia Pacific Periodical of Direction, xx (4): 423–46, doi:10.1023/A:1026373124564, S2CID 150686669

- Fung, H.H.; Cheng, S.T. (2010), "Psychology and Crumbling in the State of the Panda", Oxford Handbook of Chinese Psychology, Oxford University Press, pp. 309–26, ISBN978-0-19-954185-0

- Hamilton, G.G. (1990), "Patriarchy, Patrimonialism, and Filial Piety: A Comparing of People's republic of china and Western Europe", British Journal of Folklore, 41 (i): 77–104, doi:ten.2307/591019, JSTOR 591019

- Ho, D. Y. F. (1994), "Filial Piety, Authoritarian Moralism and Cognitive Conservatism in Chinese Societies", Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 120 (3): 349–65, hdl:10722/53184, ISSN 8756-7547, PMID 7926697

- Hsu, C.Y.; O'Connor, M.; Lee, Southward. (22 January 2009), "Understandings of Decease and Dying for People of Chinese Origin", Expiry Studies, 33 (2): 153–174, doi:10.1080/07481180802440431, PMID 19143109, S2CID 1446735

- Hsu, F.L.K. (1998), "Confucianism in Comparative Context", in Slote, Walter H.; Vos, George A. De (eds.), Confucianism and the Family, SUNY Press, pp. 53–74, ISBN978-0-7914-3736-0

- Hsu, J. (1985), "Family unit Relations, Issues and Therapy", in Tseng, West.S.; Wu, D.Y.H. (eds.), Chinese Culture and Mental Wellness, Academic Press, pp. 95–112

- Idema, Wilt L. (2009), Filial Piety and Its Divine Rewards: The Fable of Dong Yong and Weaving Maiden with Related Texts, Hackett Publishing, ISBN978-1-60384-219-8

- Ikels, C. (2004), Filial piety: Exercise and Discourse in Contemporary Eastern asia, Stanford University Press, ISBN978-0-8047-4791-2

- Hashemite kingdom of jordan, D.Yard. (1998), "Filial Piety in Taiwanese Popular Idea", in Slote, Walter H.; Vos, George A. De (eds.), Confucianism and the Family, SUNY Printing, pp. 267–84, ISBN978-0-7914-3736-0

- Rex, A.Y.; Bail, K.H. (1985), "The Confucian Paradigm of Man: A Sociological View", in Tseng, Due west.Due south.; Wu, D.Y.H. (eds.), Chinese Culture and Mental Health, Academic Printing, pp. 2–45

- Knapp, Grand.North. (2014), "Chinese Filial Cannibalism: A Silk Road Import?", in Wong, D.C.; Heldt, Gusthav (eds.), Red china and Beyond in the Mediaeval Flow: Cultural Crossings and Inter-regional Connections, Cambria Press, pp. 135–49

- Kohn, 50. (2004), "Immortal Parents and Universal Kin: Family Values in Medieval Daoism", in Chan, A.1000.; Tan, S. (eds.), Filial Piety in Chinese Thought and History, Routledge, pp. 91–109, ISBN0-203-41388-1

- Kunio, One thousand. (2004), "Filial Piety and 'Authentic Parents'", in Chan, A.K.; Tan, South. (eds.), Filial Piety in Chinese Idea and History, Routledge, pp. 111–110, ISBN0-203-41388-1

- Kutcher, N. (2006), Mourning in Late Imperial China: Filial Piety and the State, Cambridge University Printing, ISBN978-0-521-03018-two

- Kwan, K.L.Thousand. (2000), "Counseling Chinese peoples: Perspectives of Filial Piety" (PDF), Asian Journal of Counseling, 7 (1): 23–41

- Li-tian, Fang (2010), China'southward Buddhist Culture, Cengage Learning Asia, ISBN978-981-4281-42-3

- Mann, South.; Cheng, Y.Y. (2001), Nether Confucian Eyes: Writings on Gender in Chinese History, University of California Press, ISBN978-0-520-22276-ii

- Oh, Tai G. (Feb 1991), "Understanding Managerial Values and Behaviour amid the Gang of Four: Republic of korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong", Journal of Management Development, ten (2): 46–56, doi:10.1108/02621719110141095

- Schopen, K. (1997), Bones, Stones, and Buddhist Monks: Collected Papers on the Archaeology, Epigraphy, and Texts of Monastic Buddhism in India, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN978-0-8248-1870-8

- Smith, R.J. (1993), "Buddhism and the 'Keen Persecution' in China", in Keulman, Kenneth (ed.), Disquisitional Moments in Religious History, pp. 59–76

- Strong, John (1983), "Filial Piety And Buddhism: The Indian Antecedents to a "Chinese" Problem" (PDF), in Slater, P.; Wiebe, D. (eds.), Traditions in Contact and Change: Selected Proceedings of the Xivth Congress Of The International Clan for the History Of Religions, vol. 3, Wilfrid Laurier University Printing

- Sun, F.One thousand.; Long, A.; Boore, J. (February 2007), "The Attitudes of Casualty Nurses in Taiwan to Patients Who Accept Attempted Suicide", Journal of Clinical Nursing, xvi (2): 255–63, doi:x.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01479.x, PMID 17239060

- Sung, K.T. (2001), "Elderberry Respect: Exploration of Ideals and Forms in East Asia", Journal of Aging Studies, 15 (1): xiii–26, doi:ten.1016/S0890-4065(00)00014-1

- Sung, K.T. (2009a), "Chinese Immature Adults and Elder Respect Expressions in Modernistic Times", in Sung, Grand.T.; Kim, B.J. (eds.), Respect for the Elderly: Implications for Human Service Providers, Academy Press of America, pp. 179–216, ISBN978-0-7618-4530-0

- Sung, G.T. (2009b), "Repayment for Parents Kindness: Buddhist Way", in Sung, One thousand.T.; Kim, B.J. (eds.), Respect for the Elderly: Implications for Man Service Providers, Academy Printing of America, pp. 353–66, ISBN978-0-7618-4530-0

- Truitt, Allison (2015), "Not a Day but a Vu Lan Flavour: Celebrating Filial Piety in the Vietnamese Diaspora", Periodical of Asian American Studies, 18 (3): 289–311, doi:10.1353/jaas.2015.0025, S2CID 147509428

- Wang, K.T.; Yuen, M.; Slaney, R.B. (31 July 2008), "Perfectionism, Depression, Loneliness, and Life Satisfaction", The Counseling Psychologist, 37 (ii): 249–74, doi:10.1177/0011000008315975, S2CID 145670225

- Wilson, Liz (June 2014), "Buddhism and Family", Organized religion Compass, viii (6): 188–198, doi:10.1111/rec3.12107

- Whyte, M.Thousand. (2004), "Filial Obligations in Chinese Families: Paradoxes of Modernization" (PDF), in Ikels, Charlotte (ed.), Filial Piety: Practice and Discourse in Contemporary East asia, Stanford University Printing, pp. 106–27, ISBN0-8047-4790-3

- Xing, Thousand. (2012), "Chinese Translation of Buddhist Sūtras Related to Filial Piety as a Response to Confucian Criticism of Buddhists Being Unfilial", in Sharma, Anita (ed.), Buddhism in Eastern asia: Aspects of History's First Universal Religion Presented in the Modern Context, Vidyanidhi Prakashan, pp. 75–86, ISBN9789380651408

- Xing, G. (2016), "The Teaching and Practise of Filial Piety in Buddhism" (PDF), Journal of Law and Religion, 31 (ii): 212–26, ISSN 1076-9005

- Xing, G. (March 2018), "Buddhism, Practices, Applications, and Concepts - Filial Piety in Chinese Buddhism", Oxford Enquiry Encyclopedia of Religion, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.559, ISBN978-0-xix-934037-viii

- Yee, B.W.K. (2006), "Filial Piety", in Jackson, Y. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Multicultural Psychology, SAGE Publications, p. 214, ISBN978-ane-4522-6556-8

- Yim, D. (1998), "Psychocultural Features of Ancestor Worship", in Slote, Walter H.; Vos, George A. De (eds.), Confucianism and the Family unit, SUNY Press, pp. 163–86, ISBN978-0-7914-3736-0

- Zurcher, E. (2007), The Buddhist Conquest of China: The Spread and Accommodation of Buddhism in Early Medieval China (3rd ed.), Brill Publishers, ISBN978-ninety-04-15604-three

Farther reading [edit]

- Berezkin, Rostislav (21 February 2015), "Pictorial Versions of the Mulian Story in Due east Asia (Tenth–Seventeenth Centuries): On the Connections of Religious Painting and Storytelling", Fudan Periodical of the Humanities and Social Sciences, 8 (ane): 95–120, doi:10.1007/s40647-015-0060-4, S2CID 146215342

- Traylor, One thousand.L. (1988), Chinese Filial Piety, Eastern Printing

- Xing, Thou. (2005), "Filial Piety in Early Buddhism", Journal of Buddhist Ethics (12): 82–106

External links [edit]

- Xiàojing: The Classic of Filial Piety

- The Filial Piety Sutra, Buddhist discourse about the kindness of parents and the difficulty in repaying it

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Filial_piety

0 Response to "Chineese Quote if You Would Lead a Nation First Lead Your Family"

Postar um comentário